This is one of my favorite photos. It shows yours truly and the late social commentator, raconteur, and defender of atheism Christopher Hitchens at Emory University on February 26, 2010. I wish I could remember what I said that made him laugh—it must have been good.

Allison and I had actually had brief encounters with Hitchens on a couple of previous occasions; first on May 9, 2007, during his book tour in support of god Is Not Great (now considered a classic of the New Atheism), and again at the Atheist Alliance International convention in Crystal City, Virginia, which took place September 28-30, 2007. The AAI convention (marketed as “Crystal Clear Atheism”) has become legendary in the recent history of the freethought movement: it featured appearances by all of the so-called Four Horsemen (Hitchens, Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins, and Daniel Dennett), plus Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Julia Sweeney, author/filmmaker Matthew Chapman (the great-great-grandson of Charles Darwin), and a host of others. At both of these events, we stood in line with everybody else to get a book signed and just to say “Keep up the good work.” (At the Crystal City convention, I was bold enough to ask Hitchens if he would be interested in recording an interview for my brand-new venture, the American Freethought podcast, which at that time had not yet even released its first episode. He listened politely and said, “Well, I’m in the book.” At the time, I thought that was his gracious way of giving me the brush-off, but I found out a couple of years later that he was actually in the phone book! Even after that discovery, I never got around to calling the number, so I’ll never know if he would have done an interview. I think he would have, and not calling that number is one of the great regrets of my activist life.)

Then, in February 2010, we attended a public event at Emory University to celebrate their acquisition of the papers of Sir Salman Rushdie. I don’t recall the specifics of why Rushdie would give his papers to Emory, since he had no prior or obvious connection to the school; nonetheless, the agreement required him to come to Emory once a year over the course of a few years to, among other things, teach and deliver a public lecture (usually tied to the release of a new book). In this way, Allison and I were able to see Rushdie three or four times and purchase pre-signed books. At any rate, on this particular occasion, Rushdie was joined by his close friends Hitchens and the Indian-Canadian filmmaker Deepa Mehta. The moderator announced up-front that the event would not include any autograph sessions or meet-and-greets, so we did not expect to have any interaction with the participating luminaries. (Rushdie has been understandably averse to public events, especially of the glad-handing variety, after having been the target of a fatwa issued by the Ayatollah Khomeini on Valentine’s Day 1989 over perceived blasphemy in Rushdie’s novel The Satanic Verses. The fatwa has never been lifted, but Rushdie has lived more openly in recent years.)

After listening to an enjoyable roundtable discussion (including, if I recall correctly, Rushdie reciting from memory Lewis Carroll’s “The Walrus and the Carpenter,” and Hitchens countering with Wilfred Owen’s sobering anti-war poem “Dulce et Decorum Est”), we chatted with some friends before heading out, intending to eat at a pizza joint across from campus. As we left, I happened to glance down the side of the building and noticed an unmistakable profile: the Hitch had slipped out a side exit to grab a smoke.

My first thought was, “Well, they said there was no meet-and-greet, so maybe he just wants to have a smoke in peace.” But my second thought was, “Who am I kidding? Hitchens is famously garrulous, so I can’t imagine he would mind if we popped over and said a quick hello.” As we approached, I did some fast thinking to come up with something to say that wouldn’t be obvious, or cliché; something he hadn’t heard a thousand times before. (Of course, no writer hates to hear, “I’m a big fan and I loved your last book.”) Nonetheless, I quickly did a little free association: Hitchens famously likes to smoke. I grew up on a tobacco farm. Bingo.

As we approached, he glanced over with a tiny bit of apprehension, but we quickly put him at ease, introducing ourselves and thanking him for participating in the day’s events. Then I said to him, “And by the way, I wanted to thank you for my college education.” He raised a skeptical eyebrow. “How’s that?”

“Well,” I explained, “I grew up in Kentucky on a tobacco farm back in the Seventies. Nearly everyone I knew raised tobacco, and that’s how my dad saved for our college tuition. Every year, after we sold the crop at auction, he’d set aside a couple thousand each for my brother and me, and by the time I graduated from high school, I had a pretty good savings. Anyway, nowadays when I see someone smoking, I have mixed feelings. Everybody knows it’s bad for you, but at the same time, it makes me think how tobacco enabled me to get a good education and not go into a lot of debt. So… thanks!”

Hitchens nodded, looking down and absorbing what I’d just said. After a moment he took a long drag off his cigarette, then lifted it in salute as he exhaled a plume of smoke. “Much obliged,” he said with a smirk.

I don’t remember much of the conversation after that. Allison and I both asked for “selfies,” and after a couple of minutes three or four other people had wandered over. I did notice that in addition to his smoke, he was holding a drink in a white plastic cup in his other hand. I suspect it was vodka, since it smelled like alcohol but had no color. Hitch famously favored Johnnie Walker Black whiskey, but any port in a storm! As we excused ourselves, he perked up when we mentioned the pizza place. There was a brief moment when I thought he would join us. But no.

Fast forward to June 2010, which saw the publication of Hitchens’ memoir Hitch-22. His publisher announced a book tour which included Atlanta. Unbeknownst to one another, Allison and I both ordered a copy from Amazon, since we were fully planning to attend the local event and getting an autograph, so we accidently ended up with two books. As fate would have it, on the very day Hitchens was scheduled to appear on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart, he awoke in physical distress, was whisked off to an emergency room, and was given the devastating news that he was suffering from esophageal cancer. He rallied enough to do the interview, and you would never know from his performance that he had been in the hospital earlier in the day. When Jon Stewart asked him how he was doing, he quipped, “It’s too early to say,” and later joked about a time, years ago, when he was mistakenly listed as “the late Christopher Hitchens.” Nonetheless, soon thereafter he made his dire diagnosis public and announced the cancellation of the book tour.

Obviously, we were disappointed, but fully understood his need to focus on his health. As the months passed, it became common knowledge that not only was the book tour cancelled, but Hitch was well and truly in a fight for his life. In February 2011, we decided to write Hitch a letter of encouragement; at the same time, we would include one of our copies of Hitch-22 along with a return-postage-paid padded envelope and a humble request that he sign it. We figured, worst case, he’d read our letter of encouragement but we’d lose one copy of the book. We spent an hour or two composing a nice letter, and at Allison’s insistence (“It adds a human touch.”), she wrote the letter out longhand on our personal stationery.

Lo and behold, a couple of weeks later, the book came back in the mail, inscribed to us with the comment, “With thanks for your warm words and in solidarity.” Hitchens dated his signature with the odd format “12-ii-11” (i.e., February 12, 2011). We were beyond thrilled, and this book has become one of our treasured possessions.

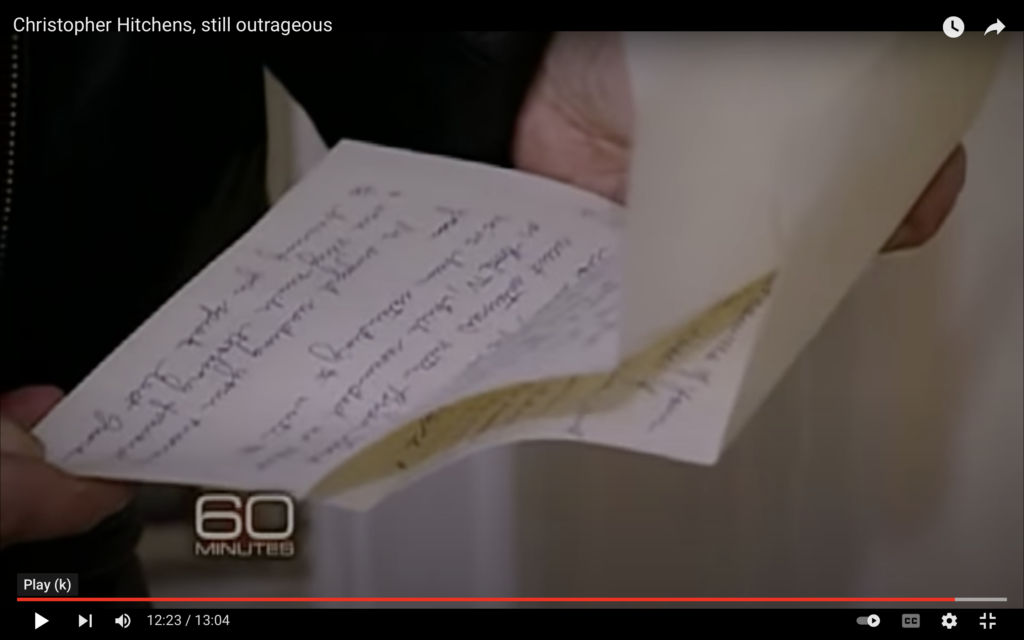

The next month (March 2011), we heard that Hitch was going to be profiled on 60 Minutes. We don’t generally watch broadcast television, but the interview was available online. We pulled it up on YouTube on our flatscreen TV and watched with interested as Steve Kroft interviewed the Hitch about his life, his controversial opinions, and the prospect of his imminent death. Toward the end of the segment, Hitch is shown perched on a window sill, wielding a letter opener as Kroft intones, “Hitchens has been deeply touched by the letters and emails he’s received, many of them offering prayers for his recovery.” The camera zooms in as Hitch silently reads a handwritten letter. Our letter. Allison recognized her own handwriting instantly. Freeze-framing the video confirmed it. We were gobsmacked! My guess is that the camera crew wanted something with visual appeal for this part of the interview, and a handwritten letter with good penwomanship on engraved stationery was a natural choice. (And it’s humbling to think that, wherever Hitchens’ papers end up, there may be our letter!)

Hitch lived for nearly another year, making occasional appearances, even participating in a couple of debates. The prospect of death and the burdens of sickness did not stop him from sharing his thoughts: he wrote several essays about the experience of dying, collected in the posthumously published Mortality. He succumbed to cancer on December 15, 2011 at the age of 62. America (yes, the Englishman Hitchens became a U.S. citizen in 2007) lost one of its great social critics, and the freethought movement lost one of its most eloquent defenders.

P.S. In early 2011, we adopted a neighbor’s cat, a very sweet, very fluffy seven-year-old Norwegian Forest mix whom we nicknamed “Hisstopher Scratchins,” much to the delight of all the veterinary staff who encountered him over the next eleven years. (Of course, none of them had a clue what this clever pun meant.) We used to joke that his favorite book was The Dog Delusion by Scratch-hard Dawkittens. He lived to the ripe old age of eighteen!